How much do taxes matter for business location, compared with other things like labor, utilities and transportation costs? As outlined in our recent State Business Tax Climate Index, an enormous amount of ink has been spilled over the years trying to definitively answer that question.Bottom line: "Taxes represent 7-13 percent of total location-sensitive costs for mannufacturing operations, and three to seven percent for non-manufacturing operations." That means, according to KPMG taxes are comparable in economic importance to both utility and transportation costs.

Observations of the legal scene from the Cornhusker State, home of Roscoe Pound and Justice Clarence Thomas' in-laws, and beyond.

Friday, March 31, 2006

Follow up: Nebraska is a high cost state. Does that matter? New KPMG study finds tax burden is up there with transport and utility costsTax Policy Blog.

Midwest area law schools make impressive gains in latest US News RankingsUS News complete ranking report requires subscription, but Tax Prof Blog helpfully summarizes the moves some law school made since last year. For area schools, the results are mostly positive (sorry SLU):

- +5 Washington University (19 in 2007)

- +5 Colorado (43)

- +30 Kansas (70)

- +25 Denver (70)

- +9 Missouri-Columbia (60)

- +7 Nebraska (70)

- - 7 St. Louis (80)

Thursday, March 30, 2006

Follow up: US Chamber of Commerce Institute of Legal Reform releases its litigation fairness index for this year; Cornhusker State maintains its #2 rankingLegal Fairness -- Where Does Your State Rank? US Chamber of commerce. See where your state ranks; Report summary (pdf). In the top ten: Nebraska, Iowa, Colorado, South Dakota. Missouri moves up in chamber's eyes for instituting tort reform last year.

follow up: United States Supreme Court denies cert on North Dakota's Missouri River suit against Army Corps of Engineers The Kansan

The 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals court ruled earlier that North Dakota could not enforce its anti-pollution laws against the corps if doing so would hamper its ability to manage Missouri River navigation. A federal law called the Clean Water Act 33 U.S.C. §§1251 et seq. ("CWA")shields the corps from lawsuits over its Missouri River management decisions, the appeals ruling said. A second case, brought by North Dakota and South Dakota, is still awaiting the Supreme Court's decision on whether it will consider it. In that dispute, the two states are challenging the same appeals court's ruling that Missouri River navigation trumps other water interests when the corps makes decisions on managing river flows.

Nebraska adopts new UCC Article 1 but retains old UCC dual good faith standards for merchants and non-merchantsContractsProf Blog

Governor Dave Heineman signed LB 570 in April 2005, which, by its terms, will take effect on January 1, 2006. LB 570, like the nine versions of Revised Article 1 already enacted in Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, Minnesota, New Mexico, Texas, and Virginia, rejects uniform R1-301, retaining the basic choice-of-law regime of pre-revised 1-105. LB 570, like the versions of Revised Article 1 enacted in four other states (Alabama, Hawaii, Idaho, and Virginia), rejects uniform R1-201(b)(20)'s definition of "good faith" as "honesty in fact and the observance of reasonable commercial standards of fair dealing," retaining the definitions set forth in pre-revised 1-201(19) (Neb. 1-201(19))and unamended (Neb.)2-103(1)(b) and 2A-103(3).

Tuesday, March 28, 2006

Nebraska court of appeals (Judge Sievers) rules that Worker Compensation Court Review Panel committed plain error in allowing dismissed insurer to intervene to appeal adverse judgment Miller v. Commercial Contractors Equip., 14 Neb. App.

606 Filed March 28, 2006. No. A-05-873. Plaintiff alleging different dates of injury sued his employer and

both insurers who might have to cover his injuries. By stipulation the parties dismissed Travelers who insured

the later dates of injuries. Travelers interpreted the stipulation to mean the Plaintiff was not alleging a new

injury's occurring during its coverage period. The trial court did find a new injury triggering Traveler's coverage and Travelers tried to intervene for the appeal. Court of appeals dismisses appeal.

Allowing an insurer to be dismissed from an action, sit by while the trial proceeds, and then file a petition in intervention after the case has been tried, a judgment has been issued, and the other parties have applied for review does not square with the analogous principle that a party cannot complain of error which that party invited the court to commit. See State v. Zima, 237 Neb. 952, 468 N.W.2d 377 (1991). Nor can a party silently tolerate error, gamble on a favorable result, and then complain of the tolerated error when the result is unfavorable. See id. In this case, Travelers got itself out of the case, the case was tried without Travelers, the result exposed Travelers' coverage, and then, at the review panel level, Travelers sought reentry into the case. Obviously, Travelers used the stipulation to secure its exit from the case--which exit would not affect the underlying liability of Commercial Contractors which Travelers is contractually obligated to cover. Thus, Travelers gambled that an award could not or would not occur which would fall within its coverage of Commercial Contractors' workers' compensation liability.

Nebraska court of appeals burns attorney generals office a little bit; State appeals sentence of probation for a child abuser but does not file brief on time; Court of Appeals does not dismiss appeal but affirms the sentence. Appeals court also rejects defendant's cross appeal that attorney general did not follow procedures to take over the appeal.State v. Rivera, 14 Neb. App. 590 Filed March 28, 2006. No. A-04-1142. If the appellant fails to file its brief within the time allowed by the rules, the Supreme Court Clerk is directed to mail a notice of default to the appellant or appellant's counsel of record. See Neb. Ct. R. of Prac. 10A (rev. 2000). Although we expect the officers of the State to adhere to the highest professional standards and to timely comply with this court's rules, we find no merit in Rivera's argument. Failure to file a brief in response to that notice subjects the appeal to dismissal. Id. Because the State filed its brief prior to issuance of any notice of default, rule 10A provides no support for dismissal of the State's appeal. See, also, State v. Campbell, 260 Neb. 1021, 620 N.W.2d 750 (2001) (although failure to comply with Nebraska Supreme Court rules may in some instances result in its not considering issue raised on appeal, failure to comply with rule requiring jurisdictional statement is not jurisdictional and does not divest court of jurisdiction).

Monday, March 27, 2006

Saturday, March 25, 2006

Nebraska supreme Court reverses defense verdict in a fire case where trial court refused to allow local fire chief to give an expert opinion on a fires cause, although the judge allowed the fire chief to give a layman's opinion, per Rule 701. Case is back up to the Supreme Court following remand in first case Perry Lumber Co. v. Durable Servs., 266 Neb. 517, 667 N.W.2d 194 (2003)..Perry Lumber Co. v. Durable Servs., S-05-005, 271 Neb. 303 (Perry II)HTMLTrial court refused to allow Holdredge fire chief to give opinion as to cause of fire even though fire chief had experience determining causes of fires and he also testified that he followed approved guidelines to determine causes of fires. The trial judge allowed the fire chief to give lay opinions, see Rule 701 but also instructed the jury that the fire chief's opinions were just lay opinions. After a verdict for the defendant, the Plaintiff appeals, and the Supreme Court reverses as the trial court did not follow its Daubert gate keeper function properly, which was prejudicial error because the trial court's instructions diluted the effectiveness of the proffered expert's testimony

We determine that the record reflects that Wagner had sufficient knowledge, skill, training, and experience to establish himself as an expert in fire investigation and was thus qualified to testify as an expert witness on issues regarding fire investigation. See, similarly, Bayse v. Tri-County Feeds, Inc., 189 Neb. 458, 203 N.W.2d 171 (1973) (permitting fire chief to testify as expert regarding origin and cause of fire).

As to the use of the standard firemans' manual for determining causes of fires, the Court finds the overwhelming acceptance of the manual meets the court's gate keeping functions: We note that Wagner and the other experts in this case generally recognized NFPA 921 as setting forth procedures by which a fire investigation is conducted. In this regard, we further note that NFPA 921 has been accepted as a methodology in other cases. See, Fireman's Fund Ins. v. Canon U.S.A., Inc., 394 F.3d 1054 (8th Cir. 2005); The court does not have to reinvent the wheel in every case: Based on the foregoing, a Daubert analysis of methodology was not necessary in this case and Perry's arguments to the contrary are unavailing. Instead of a Daubert issue, the issue before the court was whether Wagner was qualified as an expert in fire investigation. As noted above, the record demonstrates that Wagner was so qualified.Because Wagner's testimony was admissible as expert testimony, we conclude that the district court erred when it admitted Wagner's testimony only as lay witness opinion. The combination of this ruling and the court's comments to the jury relative to the admission of Wagner's testimony constituted reversible error.

Order of the Kneepads update: Nebraska Supreme Court suspends Kenyan attorney in subsequent disciplinary actions with credit for time served beyon preceding suspension but Supree Court disbars Lincoln attorney for simple neglect of casesState ex rel. Counsel for Dis. v. Muia, S-04-1375, S-05-1115, 271 Neb. 287 HTML

State ex rel. Counsel for Dis. v. Coe, S-05-744, 271 Neb. 319 HTML

Another puzzling set of attorney discipline cases from the Nebraska Supreme court. Attorney Muia already suspended for neglgecting a case and not notifying the client until the eve of the statute of limitations date for the clients case was suspended for 4 months in November 2003. Following his suspension, the attorney failed to notify all clients who had accident settlement funds in the attorneys trust account. The attorney also failed to promptly turn over a clients file on a child support case prejudicing her claim. finally the counsel for discipline charged the attorney with mishandling a business partnership with a client.

The counsel for discpline charged attorney Coe with neglectging several casea and failing to respond to discplinary grivances. The attorney did not answer the formal charges and the Supreme Court disbars him.

Muia's intial suspension in case ##State ex rel. Counsel for Dis. v. Muia, 266 Neb. 970, 670 N.W.2d 635 (2003) occurred before the effective date of revised Disciplinary Rule 16, which now requires most discplined attorneys to close their trust accounts within 30 days, in addition to notifying clients of their lost licenses. The court gets around this finding that DR2-110 applies to suspended attorneys withdrawing from employment, which would require suspended/disbarred attorneys to turn over client funds in their trust accounts, including funds intended for medical providers. Interestingly, Muia could have been charged with contempt for not notifying all clients of his suspension, but the counsel for discipline did not charge this.

The Supreme court spends most of its time justifying a suspension retroactive to the Muiua's original suspenseions ending datge. And then allows reinstatement to the Kenyan attorney as soon as he can establish a probationary program.

Coe was not so fortunate. Although he failed for several months to respond to teh counsel for discipline's grievances from five clients, he ultimately answered them after the counsel for discpline requested a temporary suspension, which the counsel for discipline withdrew. Coe did not respond to the formal charges. Rule9D requires a member to make a written response to grievances the counsel for discipline believes merit investigation. Rule 10 merely states that the respondent "shal" answer the formal charges within 30 days, as he would in any civil matter. The Supreme Court finds that neglect and failure to answer the charges warrants disbarment.

Order of the Kneepads update: Nebraska Supreme Court suspends Kenyan attorney in subsequent disciplinary actions with credit for time served beyon preceding suspension but Supree Court disbars Lincoln attorney for simple neglect of casesState ex rel. Counsel for Dis. v. Muia, S-04-1375, S-05-1115, 271 Neb. 287 HTML

State ex rel. Counsel for Dis. v. Coe, S-05-744, 271 Neb. 319 HTML

Another puzzling set of attorney discipline cases from the Nebraska Supreme court. Attorney Muia already suspended for neglgecting a case and not notifying the client until the eve of the statute of limitations date for the clients case was suspended for 4 months in November 2003. Following his suspension, the attorney failed to notify all clients who had accident settlement funds in the attorneys trust account. The attorney also failed to promptly turn over a clients file on a child support case prejudicing her claim. finally the counsel for discipline charged the attorney with mishandling a business partnership with a client.

The counsel for discpline charged attorney Coe with neglectging several casea and failing to respond to discplinary grivances. The attorney did not answer the formal charges and the Supreme Court disbars him.

Muia's intial suspension in case ##State ex rel. Counsel for Dis. v. Muia, 266 Neb. 970, 670 N.W.2d 635 (2003) occurred before the effective date of revised Disciplinary Rule 16, which now requires most discplined attorneys to close their trust accounts within 30 days, in addition to notifying clients of their lost licenses. The court gets around this finding that DR2-110 applies to suspended attorneys withdrawing from employment, which would require suspended/disbarred attorneys to turn over client funds in their trust accounts, including funds intended for medical providers. Interestingly, Muia could have been charged with contempt for not notifying all clients of his suspension, but the counsel for discipline did not charge this.

The Supreme court spends most of its time justifying a suspension retroactive to the Muiua's original suspenseions ending datge. And then allows reinstatement to the Kenyan attorney as soon as he can establish a probationary program.

Coe was not so fortunate. Although he failed for several months to respond to teh counsel for discipline's grievances from five clients, he ultimately answered them after the counsel for discpline requested a temporary suspension, which the counsel for discipline withdrew. Coe did not respond to the formal charges. Rule9D requires a member to make a written response to grievances the counsel for discipline believes merit investigation. Rule 10 merely states that the respondent "shal" answer the formal charges within 30 days, as he would in any civil matter. The Supreme Court finds that neglect and failure to answer the charges warrants disbarment. Here, Coe violated several disciplinary rules and his oath of office as an attorney, to his clients' detriment. Although the record contains some evidence concerning mental illness, Coe has ultimately failed to respond to the formal charges. We have previously disbarred attorneys who, like Coe, neglected their clients' cases and failed to cooperate with the Counsel during the disciplinary proceedings. See, e.g., State ex rel. Counsel for Dis. v. Jones, 270 Neb. 471, 704 N.W.2d 216 (2005). In particular, a pattern of neglect reveals a particular need for a strong sanction to deter others from similar misconduct, to maintain the reputation of the bar as a whole, and to protect the public. See State ex rel. NSBA v. Johnston, 251 Neb. 468, 558 N.W.2d 53 (1997). The record shows that Coe is either unable or unwilling to respond to the charges and that through a pattern of neglect, he is not fit to practice law.We have considered the undisputed allegations of the formal charges and the applicable law. Upon consideration, we find that Coe should be disbarred from the practice of law in the State of Nebraska.

Friday, March 24, 2006

Cato Institute scholar Roger Pilon speaks at UNL Law School for the Federalist Society on domestic spying Thursday March 23, Cato scholar Pilon argued that the Congress did not have legitimate authority through FISA to limit the President's inherent authority to conduct warrantless surveillance for national security purposes.

Article I Section 1 vests "All legislative powers herein granted in the Congress to which Constitution gives Congress enumerated powers."

Article II Sec 2 states the President "shall be commander in chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the militia of the several states, when called into the actual service of the United States."

Specific Congressional powers in Art 1 Section 8: "to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises, to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States"

To define and punish piracies and felonies committed on the high seas, and offenses against the law of nations;

To declare war, grant letters of marque and reprisal, and make rules concerning captures on land and water;

To raise and support armies, but no appropriation of money to that use shall be for a longer term than two years;

To provide and maintain a navy;

To make rules for the government and regulation of the land and naval forces;

To make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers, and all other powers vested by this Constitution in the government of the United States, or in any department or officer thereof.

Pilon argues that enumerated powers of Congress do not allow it to encroach on the power of the President as Commander in Chief. As commander in Chief the President must direct military forces to repel and prevent attacks.

Court cases that have touched on the issue tangentially assumed that the fourth amendment would not hinder the President's inherent authority to ensure national security. See Katz (footnote 23 and White concurring opinion) Keith, Truong. Also the FISA appeals court has upheld inherent Presidential power to conduct warrantless surveillance for national security, See In re Sealed Case, 310 F.3d 717, 742 (Foreign Intel. Surv. Ct. of Rev. 2002) (cited in Global security) (“[A]ll the other courts to have decided the issue [have] held that the President did have inherent authority to conduct warrantless searches to obtain foreign intelligence information . . . . We take for granted that the President does have that authority and, assuming that is so, FISA could not encroach on the President’s constitutional power.”) (emphasis added); accord, e.g., United States v. Truong Dinh Hung, 629 F.2d 908 (4th Cir. 1980); United States v. Butenko, 494 F.2d 593 (3d Cir. 1974) (en banc); United States v. Brown, 484 F.2d 418 (5th Cir. 1973).

Tuesday, March 21, 2006

Follow up: Nebraska Court of Appeals (J. Carlson) allows State Patrolman's stress-induced suicide worker compensation case to proceed over Attorney General's 12b6 motion.Zach v. Nebraska State Patrol, 14 Neb. App. 579 March 21, 2006. A-05-449. State patrolman who had pulled over Norfolk bank robbers in 2002 but mistakenly let them go committed suicide after learning of his error. Estate sued for worker compensation alleging that chemical alterations to his brain that the stressful news induced led to his suicide. Trial judge dismissed petition on State's 12(b)(6) motion. Review panel reversed and court of appeals agrees that a 12(b)(6) dismissal for either a job related accident or occupational disease theory is premature. Judge Cassel dissents

Interesting, courts assume that civil pleading rules, especially 12b6 would apply to pleadings in the worker compensation court, although 48-173 prescribes the necessary pleadings in a worker compensation case. Nevertheless, Appeals court holds, with Judg e Cassel dissenting, that at the pleading stage it would be premature to say categorically that stress induced chemical changes to the brain, if any, would not be "(violent events) to the physical structure of the body." See § 48-151(4) defining "Injury."

Dissenting Judge Cassel finds it impossible that allegations could ever support a comp claim

The (plaintiffs') argument recognizes that the act of suicide cannot constitute the "violence to the physical structure of the body" necessary to establish an "injury" within the meaning of the statute. Once there has been a compensable "injury," i.e., once the "violence to the physical structure of the body" has occurred, then it becomes possible that the subsequent act of suicide is a consequence naturally flowing from the injury. To supply the required allegation of "injury," the appellees depend upon the allegation of "physical changes" to Zach's brain...Because I disagree that the bare allegation of "physical changes" to Zach's brain is sufficient to set forth a claim of a compensable "injury," I respectfully dissent..

Sunday, March 19, 2006

Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals rules under Nebraska law insurer for owner of vehicle in accident is primary insurer; secondary insurer of driver's employer did not waive equitable subrogation for amounts spent defending employer and settling its claimNational. American Ins. v. Republic Western Insurance 03/10/06 U.S. Court of Appeals #053037P.pdf District of Nebraska. Grain truck driver an employee of Grain company ran a stop sign and severely injured a motorist in North Dakota. Grain Company did not own the truck, rather Colberg Transportation owned the truck. Eventually the parties settled with the injured driver for $600K. Republic Western insured the vehicle. National American insured the drivers employer and paid $25000 of the settlement. Vehicle insurer Republic refused to National Americans offer to defend drivers employer. District Court Judge Camp found vehicle insurer Republic the primary insurer and also found that National American was entitled to subrogation of its defense and settlement costs. Eighth Circuit affirms.

Eight circuit upholds ruling that vehicle's insurance is primary and there was no joint venture Inded under Nebraska law, the vehicle owner’s insurance provides primary coverage. See Turpin v. Standard Reliance Ins. Co., 99 N.W.2d 26, 37 (Neb. 1959). Because Republic Western fails to prove the jointventure constituted an “Insured contract,” and under Nebraska la the primaryinsurance follows the vehicle, the distict court did not err in determining theRepublic Western policy provides primary coverage and the National American policy was excess

Eighth Circuit finds there was no waiver of subrogation whether or not excess insurer National American formally "reserved its rights," nor whether or not excess insurer National American preseved its equitable subrogation rights in the settlement docuements

An insurer does not waive its right to subrogation against another insurer based on the first insurer’sconduct with its own insured. See St. Paul Mercury Ins. Co. v. Lexington Ins. Co.,

78 F.3d 202, 208 (5th Cir. 1996) (holding primary and excess insurers who defended

the insured did not waive their right to rely on “other insurance” clauses in their

policies by failing to reserve that right); Attorneys Liab. Prot. Soc’y v. Reliance Ins.

Co., 117 F. Supp. 2d 1114, 1122 (D. Kan. 2000) (concluding that because a

reservation of rights is an agreement “between the insurer and the insured, the

insurer’s failure to obtain such an agreement does not bar a contribution claim against

a co-insurer”)

As the primary insurer, Republic Western had a duty to provide (employer) W & G’s

defense and pay any sums for which (employer) W & G was liable to (Injury case Plaintiff). (Excess insurer) National American tendered (employer's) W & G’s defense to (primary insurer) Republic Western, but Republic Western declined to defend W & G. Accordingly, Republic Western is liable as primaryinsurer for the amounts National American incurred for W & G’s defense and insettlement of the Quellhorst personal injury action.

Friday, March 17, 2006

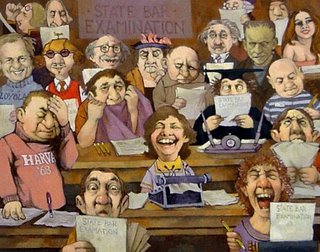

Nationwide bar exam pass rates are fallingBar Exam Failures Are on the Rise, Law.com. California's has always been one of the toughest bar examinations to pass. Just 44 percent passed the test in 2004, the latest year that numbers were available from the National Conference of Bar Examiners. But nationwide, some 28,110 people failed the test in 2004, for a 64 percent pass rate. By comparison, 65 percent passed in 2000 and 70 percent passed in 1995.

What is the reason for a lower pass rate nationwide?

**More desirable states impose tougher standards, for example some "sunbelt" states wanted to make it hard for semi-retired lawyers to move into their states.

**there are more students graduating from unaccredited law schools, especially in California.

**Law schools don't see their job as preparing students for the bar exam.Indeed, the situation has become such a concern that law schools have begun implementing for-credit bar review courses into their curricula.

**Did the law.com article mention anywhere minority students' taking and failing the exam? NO

Since 1995, the number of people failing the test has ballooned by 28 percent, while the number of law graduates taking the bar exam has increased by 6.4 percent, according to the NCBE. In 2004, some 77,246 people sat for the bar exam, compared to 72,591 in 1995; Nebraska stats here.

Nebraska State Bar Examination Passing Rates: 1981 and ten year summary (1995-2004) of overall and first time passing

Nebraska 1981 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004

Overall 89% 90% 90% 86% 84% 88% 81% 82% 76% 79% 77%

First-Time 90% 92% 94% 88% 86% 89% 85% 84% 81% 84% 86%

Statistics for February and July 2004 Nebraska State Bar Examinations

Nationwide bar exam pass rates are fallingBar Exam Failures Are on the Rise, Law.com. California's has always been one of the toughest bar examinations to pass. Just 44 percent passed the test in 2004, the latest year that numbers were available from the National Conference of Bar Examiners. But nationwide, some 28,110 people failed the test in 2004, for a 64 percent pass rate. By comparison, 65 percent passed in 2000 and 70 percent passed in 1995.

What is the reason for a lower pass rate nationwide?

**More desirable states impose tougher standards, for example some "sunbelt" states wanted to make it hard for semi-retired lawyers to move into their states.

**there are more students graduating from unaccredited law schools, especially in California.

**Law schools don't see their job as preparing students for the bar exam.Indeed, the situation has become such a concern that law schools have begun implementing for-credit bar review courses into their curricula.

**Did the law.com article mention anywhere minority students' taking and failing the exam? NO

Since 1995, the number of people failing the test has ballooned by 28 percent, while the number of law graduates taking the bar exam has increased by 6.4 percent, according to the NCBE. In 2004, some 77,246 people sat for the bar exam, compared to 72,591 in 1995; Nebraska stats here.

Nebraska State Bar Examination Passing Rates: 1981 and ten year summary (1995-2004) of overall and first time passing

Nebraska 1981 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004

Overall 89% 90% 90% 86% 84% 88% 81% 82% 76% 79% 77%

First-Time 90% 92% 94% 88% 86% 89% 85% 84% 81% 84% 86%

Statistics for February and July 2004 Nebraska State Bar Examinations

- Feb 33%

- July 83%

- total 77%

- ABA lawschool graduates 77%

- Taking test 1st time feb 55%

- Taking test 1st time jul 88%

- repeating test feb 19%

- repeating test jul 33%

Tuesday, March 14, 2006

Nebraska court of appeals (J. Moore) reverses neglect adjudications for indian children where the state failed to plead specifically that State had taken "active measures" to prevent breakup of Indian family, per 43-1505(4) RRs Neb

In re Interest of Dakota L. et al., 14 Neb. App. 559 Filed March 14, 2006. No. A-05-385.

In action for taking juvenile court jurisdiction over children who were members of Macy Indian Tribe but currently resided in Douglas County the Court adjudicated the children as neglected juveniles. The States initial petition did not plead specific allegations however that the Indian child welfare act (25 U.S.C. § 1911(a) (2000) federal ICWA; Neb. Rev. Stat. § 43-1504(1) (Reissue 2004) Nebraska ICWA) requires that the State had taken "active measures" to keep the Indian family intact. The State did file an amended petition that contained the necessary language from 43-1505(4) but the court proceeded with the original defective petition.

Any party seeking to effect a foster care placement of, or termination of parental rights to, an Indian child under state law shall satisfy the court that active efforts have been made to provide remedial services and rehabilitative programs designed to prevent the breakup of the Indian family and that these efforts have proved unsuccessful. neither original nor amdned petition made these allegations.

Further 43-1505(5) requires that any foster care placement order requires the court determine by clear and convincing evidence, including testimony of qualified expert witnesses, that the continued custody of the child by the parent or Indian custodian is likely to result in serious emotional or physical damage to the child.

"In an action for adjudication of Indian children, it is necessary to plead facts under the ICWA. In this case, while the State did file an amended petition including allegations required under the ICWA, the court did not adjudicate the children under the amended petition. It was error for the court to proceed on the adjudication under the original petition, which did not allege facts under the ICWA. "we reverse the order of adjudication and remand the cause to the juvenile court for an adjudication under an appropriate amended petition, with directions to the court to make specific findings as required by § 43-1505." In re Interest of Sabrienia B., 9 Neb. App. 888, 621 N.W.2d 836 (2001)

Saturday, March 11, 2006

Hopefully todays case will relieve counties of the need to appoint costly post conviction counsel to pursue claims of ineffectiveness when defendants who pled guilty receive lawful and justifiable sentences and did not file timely but frivolous appeals. Nebraska Supreme Court (J Wright) rules that for defendants to receive direct appeals there should be nonfrivolous grounds for appeal that would indicate a defendants interest in an appeal.State v. Wagner, 271 Neb. 253 Filed March 10, 2006. No. S-04-1104. Defendant sentenced on a plea bargain to prison for murder sought post conviction relief to file a direct appeal. Trial court found no expressinterest from defendant to appeal and overruled motion. Following Supreme Court Roe v. Flores Ortega case, court rejects "bright line rule" to order an appeal every time a defendant belatedly requests one. Instead the standard must be "reasonable probability" that the defendant would have requested appeal, especially if there were non-frivolous issues to appeal. Roe v Flores Ortega set the standard for effectiveness of counsel on whether to appeal a conviction to be "when there is reason to think either (1) that a rational defendant would want to appeal (for example, because there are nonfrivolous grounds for appeal), or (2) that this particular defendant reasonably demonstrated to counsel that he was interested in appealing." Likewise Flores-Ortega standard for prejudice in causing the forfeiture of appeal is "a reasonable probability that, but for counsel’s deficient failure to consult with him about an appeal, he would have timely appealed."

To show prejudice related to the failure to file an appeal, "a defendant must demonstrate that there is a reasonable probability that, but for counsel's deficient failure to consult with him about an appeal, he would have timely appealed." Roe v. Flores-Ortega, 528 U.S. 470, 484, 120 S. Ct. 1029, 145 L. Ed. 2d 985 (2000). Whether a defendant meets his burden depends on the facts of a particular case. "[E]vidence that there were nonfrivolous grounds for appeal or that the defendant in question promptly expressed a desire to appeal will often be highly relevant in making this determination." 528 U.S. at 485.But such evidence alone is insufficient to establish that, had the defendant received reasonable advice from counsel about the appeal, he would have instructed his counsel to file an appeal. Roe v. Flores-Ortega, 528 U.S. at 486.

Wagner's sentences were within the statutory ranges. Sentences within statutory limits will be disturbed by an appellate court only if the sentences complained of were an abuse of judicial discretion. State v. Cook, 266 Neb. 465, 667 N.W.2d 201 (2003). Wagner had no nonfrivolous basis for an appeal, and thus, he has not shown that he was prejudiced by the fact that no appeal was filed. He also has not shown there was a reasonable probability that he would have timely appealed but for the fact that counsel did not specifically consult with him about an appeal.

Friday, March 10, 2006

Follow up: Nebraska Supreme Court on further review reverses Court of Appeals decision to order a new trial when prosecutor failed to disclose a purportedly exculpatory witness statement; Supreme Court (J Miller-Lerman) appears to reject a statutory standard under 29-2001 that would be more lenient to defendants than the Brady standard as the US Supreme Court currently assesses alleged Brady violationsState v Lykens Filed March 10, 2006. No. S-04-844; court of appeals decision reversed. The Court of Appeals had reversed Lykens verdict because the defendant and his attorney discovered after trial that the Fremont police had an exculpatory statement from a witness that the state failed to disclose. The Court of Appeals ruled that the standard for a new trial for failure to disclose evidence was under state statute and federal constitutional law is "when the evidence alleged to be newly discovered was withheld by the State, a defendant is entitled to a new trial if the omitted evidence could have created a reasonable doubt that he or she committed the alleged crime or crimes. (emphasis supplied)" The Supreme Court reverses and finds the standard should be "whether the nature of the evidence at issue was such that the State's failure to disclose it to (Def) prior to trial violated Def's due process rights.

In this case, the evidence was not material under the Bagley standard (United States v. Bagley, 473 U.S. 667 , 105 S. Ct. 3375, 87 L. Ed. 2d 481 (1985)'superseding United States v. Agurs, 427 U.S. 97 96 S. Ct. 2392, 49 L. Ed. 2d 342 (1976)and that therefore, the State's failure to disclose it did not violate Lykens' due process rights and was not a sufficiently serious nondisclosure so as to arise to a Brady 373 U.S. 83 violation. Therefore, the district court did not abuse its discretion by denying Lykens' supplemental motion for new trial, and the Court of Appeals' conclusion to the contrary was error.

The interview evidence was not of an impeaching nature, nor did it serve directly to exculpate Lykens.

Brainard's interview did not deny Lykens a fair trial, and on the contrary, the guilty verdict is worthy of confidence. See Kyles v. Whitley, 514 U.S. 419, 434, 115 S. Ct. 1555, 131 L. Ed. 2d 490 (1995) {standard is a verdict worthy of confidence} We conclude that there is not a reasonable probability that had the evidence been disclosed to the defense, the result of the proceeding would have been different. We conclude there was no Brady 373 U.S. 83 violation.

Thursday, March 09, 2006

Nebraska Supreme Court (J Stephan) requires courts to use straight line depreciation to determine self employed parents' income for child support before ordering deviations to the guidelines Family Law Professor Blog reports the Nebraska Supreme Court reversed an Otoe County divorce case where the trial court determined the farmer-father's income by arbitrarily adding back income when the father's accountant used "declining balance" depreciation for the father's tax returns. Gress v. Gress 271 Neb. 122 March 3, 2006. No. S-05-007. Child Support guidelines, Para D allows courts to consider depreciation when determining child support, but if the court does it must use "straight line depreciation." The Court rules that courts when agreeing to consider depreciation, must first determine what the parents income would be from this intitial calculation, and them if deviations are appropriate, the court must make these findings "in the best interests of the children."

This is our first opportunity to review a case involving the proper treatment of depreciation deductions under the September 2002 amendment to paragraph D. Interpretation of the Nebraska Child Support Guidelines presents a question of law, regarding which an appellate court is obligated to reach a conclusion independent of the determination reached by the court below. Mathews v. Mathews, 267 Neb. 604, 676 N.W.2d 42 (2004) once a potential child support obligation has been determined based upon the calculations under paragraph D, paragraph C permits a deviation from the guidelines "whenever the application of the guidelines in an individual case would be unjust or inappropriate." See, Kalkowski v. Kalkowski, 258 Neb. 1035, 607 N.W.2d 517 (2000); because there is no record of what amount of child support Patrick would be required to pay based upon proper calculation of his depreciated income under paragraph D or why it would not be in the best interests of the children to order Patrick to pay that amountthe court reverses;

Tuesday, March 07, 2006

Nebraska Court of Appeals (J. Sievers) holds that under "old" worker comp subrogation law (48-118 RRS Neb) Plaintiff in personal injury suit does not have standing to assert rights of the subrogated insurerErikson v. Abels (Not Designated for Permanent Publication) March 7, 2006. No. A-04-673. This case brings the court back to the "old" 48-118, the worker compensation subrogation law that directed "dollar for dollar" subrogation from a third party claim. The Plaintiff in this case, although she lost, tries to use that rule to salvage something out of her unsuccessful verdict in a car accident case.

Plaintiff sued defendant for injuries from auto accident that occurred in 1990. Court of appeals in 2002 reversed first defense verdict on "range of vision" rule. Retrial also resulted in defense verdict. Court of appeals, somewhat perplexed by the plaintiff's appeal figures out Plaintiff's argument to be that he should be allowed to add on the worker comp subrogation claim and that the defendant somehow was strictly liable for the plaintiff's worker compensation costs.

Plaintiff lacked standing to object to whether the trial court's handling of the subrogated worker comp insurer's rights was proper

Nebraska Court of Appeals (J. Sievers) holds that under "old" worker comp subrogation law (48-118 RRS Neb) Plaintiff in personal injury suit does not have standing to assert rights of the subrogated insurerErikson v. Abels (Not Designated for Permanent Publication) March 7, 2006. No. A-04-673. This case brings the court back to the "old" 48-118, the worker compensation subrogation law that directed "dollar for dollar" subrogation from a third party claim. The Plaintiff in this case, although she lost, tries to use that rule to salvage something out of her unsuccessful verdict in a car accident case.

Plaintiff sued defendant for injuries from auto accident that occurred in 1990. Court of appeals in 2002 reversed first defense verdict on "range of vision" rule. Retrial also resulted in defense verdict. Court of appeals, somewhat perplexed by the plaintiff's appeal figures out Plaintiff's argument to be that he should be allowed to add on the worker comp subrogation claim and that the defendant somehow was strictly liable for the plaintiff's worker compensation costs.

Plaintiff lacked standing to object to whether the trial court's handling of the subrogated worker comp insurer's rights was proper

The statutory right of subrogation belongs to Travelers, not to Erikson, by the plain language of § 48-118. The statutory scheme is easily summarized: Travelers can either "join" in and actively "prosecute" its subrogation claim as provided by § 48-118 or sit on the sidelines, allow Erikson to prosecute the claim, and then receive its share of the recovery and pay its share of the expensesCourt of appeals determines from Plaintiff's appeal that a third party defendant in an injury case is not strictly liable for injuries to a worker injured in the course and scope of employment

Erikson asserts that the trial court erred in finding that Abels "was not liable to Defendant [Travelers] on its subrogation claim for the workers' compensation benefits it paid to [Harold]." We are unaware of any such finding by the trial court, and Erikson's brief does not direct us to any such finding in the record.. Plaintiff's argument is that (worker comp insurer) was entitled to a verdict equal to the amount of benefits paid to and for Harold, irrespective of what the jury might award Plaintiff... Pl. appears to lack standing to assert a claim belonging to worker comp insurer and worker comp insurer has not appealed... In Neumann v. American Family Ins., 5 Neb. App. 704, 713, 563 N.W.2d 791, 796 (1997), we held that because of the statutory mandate that the employee was entitled to the "excess" over the subrogation interest of the insurer, the district court erred, as a matter of law, in attempting to equitably divide the $118,000 paid to the injured employee by the tort-feasors. Thus, in Neumann, there was no "excess" for the employee, whereas in the instant case, there are no "first dollars" for Travelers and no "excess" for Erikson, because the jury awarded nothing. For multiple reasons, this assignment of error in without merit.

Monday, March 06, 2006

Nebraska Supreme Court (J Miller-Lerman) allows tort claim against Lancaster County District Court clerk for disregarding perfected attorney lien when distributing judgment client's adverse party paid into court.Stover v. County of Lancaster, 271 Neb. 107 March 3, 2006. No. S-04-1108.

Attorney handled divorce case and filed attorney lien per 7-108 with client's adverse party and the court file. Adverse party paid a property settlement into the court, see §25-2214.01. District Court clerk disregarded attorney lien. Trial court dismissed attorney's tort claim ruling that attorney should have filed a complaint for intervention to seek claim to property settlement funds. Supreme Court in an issue of first impression holds that perfection of attorney lien in accordance with 7-108 preserves lien through adverse party's transferring judgment debt to the court clerk, notwithstanding 25=2214.01.. Problem: Apparently attorney also filed a copy of her lien in the District Court file, court does not state that this was a necessary step in perfecting her attorney lien. Furthermore not discussed in opinion, decision assumes this was a negligence case against the County court, what if the court distributing a judgment intentionally disregarded an attorney lien?

Given our decisions regarding attorneys' liens, and harmonizing §§ 7-108 and 25-2214.01, we conclude that when an adverse party pays into the clerk of the district court such sums as will satisfy a judgment awarded against that party, and prior to the payment of such sums into the court, notice is given and an attorney's lien has attached, the district court clerk who has notice of the lien by virtue of its filing has a duty to retain that portion of the deposited funds to which an attorney's lien has attached until the "rightful owner" of the sums retained can be determined. Under such circumstances, when the funds cannot be fully paid out, as part of the clerk's duty to "manage" such funds, the clerk of the district court should notify those entities of whom the clerk is on notice who have claimed an interest in the funds, of the retention of the funds, to effectuate the determination of the "rightful owner." § 25-2214.01

Saturday, March 04, 2006

A ringing victory for religious toleration and multiculturalism from Canada: Canadian Supreme Court rules that Sikh children may bring knives to school. ACLU are you doing enough to keep up with our freer Northern neighbors?Multani v. Commission scolaire Marguerite-Bourgeoys 2006 SCC 6 20060302 docket 30322

I think our squishy SCOTUS members who are so enamored of "foreign law" should take a few cues from their Canadian Supreme Court counterparts. I think schools in America are too concerned about safety after Columbine 1999. After all if more students had been armed a few goth cranks would not have been able to terrorize an entire school. Canoe Network.

The Supreme Court of Canada struck down a Montreal school board's ban on the wearing of ceremonial daggers by Sikh students - delivering a ringing defence of religious freedom in the process.In an 8-0 judgment Thursday, the court quashed a decision that barred teenager Gurbaj Singh Multani from attending class wearing the dagger, known as a kirpan.The court left room for some restrictions on kirpans in the name of public safety. But a blanket ban goes too far and violates the Charter of Rights, wrote Justice Louise Charron. NB Earlier this year a Judge in Detroit dismissed a weapons charge against a Sikh college student at Wayne State for carrying the kirpan under similar conditions. release

G and his father B are orthodox Sikhs. G believes that his religion requires him to wear a kirpan at all times; a kirpan is a religious object that resembles a dagger and must be made of metal. In 2001, G accidentally dropped the kirpan he was wearing under his clothes in the yard of the school he was attending. The school board sent G’s parents a letter in which, as a reasonable accommodation, it authorized their son to wear his kirpan to school provided that he complied with certain conditions to ensure that it was sealed inside his clothing. G and his parents agreed to this arrangement. The School District reversed the board decision and would not allow the boy to wear an authentic Kirpan. The parents sued. The Superior Court granted the motion, declared the decision to be null, and authorized G to wear his kirpan under certain conditions.The risk of G using his kirpan for violent purposes or of another student taking it away from him is very low, especially if the kirpan is worn under conditions such as were imposed by the Superior Court.Furthermore, there are many objects in schools that could be used to commit violent acts and that are much more easily obtained by students, such as scissors, pencils and baseball bats. The evidence also reveals that not a single violent incident related to the presence of kirpans in schools has been reported. Although it is not necessary to wait for harm to be done before acting, the existence of concerns relating to safety must be unequivocally established for the infringement of a constitutional right to be justified. Nor does the evidence support the argument that allowing G to wear his kirpan to school could have a ripple effect. Lastly, the argument that the wearing of kirpans should be prohibited because the kirpan is a symbol of violence and because it sends the message that using force is necessary to assert rights and resolve conflict is not only contradicted by the evidence regarding the symbolic nature of the kirpan, but is also disrespectful to believers in the

A ringing victory for religious toleration and multiculturalism from Canada: Canadian Supreme Court rules that Sikh children may bring knives to school. ACLU are you doing enough to keep up with our freer Northern neighbors?Multani v. Commission scolaire Marguerite-Bourgeoys 2006 SCC 6 20060302 docket 30322

I think our squishy SCOTUS members who are so enamored of "foreign law" should take a few cues from their Canadian Supreme Court counterparts. I think schools in America are too concerned about safety after Columbine 1999. After all if more students had been armed a few goth cranks would not have been able to terrorize an entire school. Canoe Network.

The Supreme Court of Canada struck down a Montreal school board's ban on the wearing of ceremonial daggers by Sikh students - delivering a ringing defence of religious freedom in the process.In an 8-0 judgment Thursday, the court quashed a decision that barred teenager Gurbaj Singh Multani from attending class wearing the dagger, known as a kirpan.The court left room for some restrictions on kirpans in the name of public safety. But a blanket ban goes too far and violates the Charter of Rights, wrote Justice Louise Charron. NB Earlier this year a Judge in Detroit dismissed a weapons charge against a Sikh college student at Wayne State for carrying the kirpan under similar conditions. release

G and his father B are orthodox Sikhs. G believes that his religion requires him to wear a kirpan at all times; a kirpan is a religious object that resembles a dagger and must be made of metal. In 2001, G accidentally dropped the kirpan he was wearing under his clothes in the yard of the school he was attending. The school board sent G’s parents a letter in which, as a reasonable accommodation, it authorized their son to wear his kirpan to school provided that he complied with certain conditions to ensure that it was sealed inside his clothing. G and his parents agreed to this arrangement. The School District reversed the board decision and would not allow the boy to wear an authentic Kirpan. The parents sued. The Superior Court granted the motion, declared the decision to be null, and authorized G to wear his kirpan under certain conditions.The risk of G using his kirpan for violent purposes or of another student taking it away from him is very low, especially if the kirpan is worn under conditions such as were imposed by the Superior Court.Furthermore, there are many objects in schools that could be used to commit violent acts and that are much more easily obtained by students, such as scissors, pencils and baseball bats. The evidence also reveals that not a single violent incident related to the presence of kirpans in schools has been reported. Although it is not necessary to wait for harm to be done before acting, the existence of concerns relating to safety must be unequivocally established for the infringement of a constitutional right to be justified. Nor does the evidence support the argument that allowing G to wear his kirpan to school could have a ripple effect. Lastly, the argument that the wearing of kirpans should be prohibited because the kirpan is a symbol of violence and because it sends the message that using force is necessary to assert rights and resolve conflict is not only contradicted by the evidence regarding the symbolic nature of the kirpan, but is also disrespectful to believers in the  Sikh

Sikh religion and does not take into account Canadian values based on multiculturalism.

religion and does not take into account Canadian values based on multiculturalism.

Friday, March 03, 2006

Nebraska Supreme Court dismisses guardianship and State administrative personnel cases for lack of jurisdiction

Kaplan v. McClurg, 271 Neb. 101 Filed March 3, 2006. No. S-04-1097.

In re Guardianship of Sophia M., S-05-154, 271 Neb. 133

McClurg: Staff attorneys for Nebraska Department of Health sought to prevent reclassification of their jobs. District Court dismissed their action because there was no adverse action the State had taken against the staff attorneys. Supreme Court affirms as there was no jurisdiction to review this personnel action.

Sophia M. No appeal from order for a Rule 35 mental/physical exam in a guardianship case. Although guardianships are special proceedings, the discovery order was not a final order. The trial court had jurisdiction after filing notice ofappeal from a non-appealable order

MClurg: For purposes of the APA, a "[c]ontested case" is defined as "a proceeding before an agency in which the legal rights, duties, or privileges of specific parties are required by law or constitutional right to be determined after an agency hearing." § 84-901(3). The parties did not petition DAS for a declaratory order "as to the applicability to specified circumstances of a statute, rule, regulation, or order within the primary jurisdiction of the agency." See § 84-912.01(1) and 10 Neb. Admin. Code, ch. 20, § 008.01. Thus, § 84-912.01 did not require a hearing before DAS to decide the issues raised by the petitioners, the petition for a declaratory order did not require DAS to act in a quasi-judicial manner, and the proceeding was not a contested case under the APA

Sophia M.: A rule 35 order does not affect a substantial right and, therefore, is not a final, appealable order.A notice of appeal from a nonappealable order does not render void for lack of jurisdiction acts of the trial court taken in the interval between the filing of the notice and the dismissal of the appeal by the appellate court. In re Guardianship & Conservatorship of Woltemath, 268 Neb. 33, 680 N.W.2d 142 (2004).

Nebraska Supreme Court (J. Stephan) affirms defense verdict in attorney malpractice action; Although attorney might have failed to renew client's security interest in collateral, plaintiff still could have sued personally the owners of the purchasing business because lapsed financing statement, impairing the collateral, did not discharge those co-makers' debtBorley Storage & Transfer Co. v. Whitted, 271 Neb. 84 Filed March 3, 2006. No. S-04-708 (Borley Storage II) earlier opinion

Plaintiff sold his business and the purchasers agreed to pay for the business through payments on a note secured with the purchasers assets. The plaintiff alleged his attorney failed to renew the financing statement after five years and did not tell him to do it. Years later the purchasers defaulted and filed bankruptcy. Because another creditor filed an intervening security interest in the purchasers property the Plaintiff lost most of the value of his collateral. Plaintiff did not sue the owners who also signed the note because Plaintiff argued the lapsed financing statement discharged the owners obligation on the note. See old UCC3-606 {impairment of collateral defense.} Earlier supreme court decision reversed summary judgment for the Plaintiff because there was no bill of exceptions. Jury verdict was for defendant attorney and plaintiff again appeals to Supreme Court AFFIRMED

Even if allowing a security interest to lapse is "impairment of collateral" Old 3-606 does not allow co-makers to a discharge on the note

§ 3-606 (now 3-605) generally protected a surety's right of subrogation. See 61 A.L.R. 5th, Annot., 61 A.L.R. 5th 525 (1998); 21 Shepard's Causes of Action 145, § 23 (1990).Supreme Court followed the majority view that the impairment of collateral defense is not available to the maker or comaker of a promissory note. See Ashland State Bank v. Elkhorn Racquetball, Inc., 246 Neb. 411, 419, 520 N.W.2d 189, 194 (1994) {rejected a claim that a party was entitled to assert "the special suretyship defenses set forth in Neb. U.C.C. § 3-606" based in part upon our prior determination that the party "was a principal obligor on the note and not an accommodation party."}

Under old UCC 3-415 (new 3-419) the owners of the purchasing business were co-makers to the note and were naccommodatinging or surety partiesNeWhetherher a party is an accommodation maker or a principal obligor on an instrument is a question of intent. Ashland State Bank v. Elkhorn Racquetball, Inc., supra; Marvin E. Jewell & Co. v. Thomas, 231 Neb. 1, 434 N.W.2d 532 (1989) U.C.C. § 3-415 (Reissue 1980) The only reasonable inference which can be drawn from the record is that the Bauders were principal obligors of the promissory note, not accommodation parties, and thus could not have asserted an impairment of collateral defense to a claim on the note. Accordingly, the district court did not err in determining as a matter of law that the Bauders were personally liable on the note notwithstanding the failure to file a continuation statement, and in so instructing the jury.

The plaintiffs failed to mitigate their damages, and further the jury did not believe that the attorney committed malpractice

Court allowed evidence of habit per defendant attorneys testimony to prove point that attorney would have informed the client to renew security interests in five years. § 27-406 and Hoffart v. Hodge, 9 Neb. App. 161, 609 N.W.2d 397 (2000) We agree with the analytical principles applied by the Court of Appeals in Hoffart v. Hodge, 9 Neb. App. 161, 609 N.W.2d 397 (2000), and conclude that the district court did not abuse its discretion in permitting this testimony. As in Hoffart, this case focuses on a professional service rendered years prior to testimony in a malpractice action. In Hoffart, the court recognized the practical reality that "a doctor cannot be expected to specifically recall the advice or explanation he or she gives to each and every patient he or she sees or treats" and that thus, "evidence of habit may be the only vehicle available for a doctor to prove that he or she acted in a particular way on a particular occasion" and is therefore "highly relevant." 9 Neb. App. at 168, 609 N.W.2d at 404. The same reality exists with respect to advice which is routinely given by a lawyer to a client in particular circumstances.

Wednesday, March 01, 2006

Will Nebraska's 4.58 SBTCI get us into the BCS next year? Nebraska ranks 44th (out of 50) least favorable for business tax policiesThe Tax Foundation. The Tax Foundation's "State Business Tax Climate Index" (SBTCI) rates how favorable overall tax policies are in each state. Complete report, 56 pages pdf format here. Did you know that most job migration is between states with higher taxes to lower ones, rather than to overseas labor markets? " State lawmakers must be aware of how their state’s business climate matches up to their immediate neighbors and to other states within their region. " Tax incentives ala LB 775 are not the answer either:

Will Nebraska's 4.58 SBTCI get us into the BCS next year? Nebraska ranks 44th (out of 50) least favorable for business tax policiesThe Tax Foundation. The Tax Foundation's "State Business Tax Climate Index" (SBTCI) rates how favorable overall tax policies are in each state. Complete report, 56 pages pdf format here. Did you know that most job migration is between states with higher taxes to lower ones, rather than to overseas labor markets? " State lawmakers must be aware of how their state’s business climate matches up to their immediate neighbors and to other states within their region. " Tax incentives ala LB 775 are not the answer either:

In July of 2004 Florida lawmakers cried foul because a major credit card company announced it would close its Tampa call center, lay off 1,110workers, and outsource those jobs to another company. The reason for thelawmakers’ ire was that the company had been lured to Florida with a generous tax incentive package and had enjoyed nearly $3 million worth of tax breaks during the past nine years.Usually states offer generous tax incentives to paper over an unfavorable tax climate:

If a state needs to offer such (incentive) packages, it is most likely covering for a woeful business climate plagued by bad tax policy. A far more effective approach is to systematically improve the business climate for the long term so as to improve the state’s competitiveness as compared to other statesWhat makes up a good state tax policy? It must be broad, low and fair to all businesses, in other words it shouldnt play favorites:

Good state tax systems levy low, flat rates on the broadest bases possible, and they treat all taxpayers the same. Variation in the tax treatment of different industries favors one economic activity or decision over another. The more riddled a tax system is with these politically motivated preferences the less likely it is that business decisions will be made in response to market forces.Heres the kicker, guess who is in the "bottom ten" for good tax policy: 1. Wyoming 2. South Dakota 3. Alaska 4. Florida 5. Nevada 6. New Hampshire 7. Texas 8. Delaware 9. Montana 10. Oregon The ten worst states in the SBTCI are as follows: 41. Arkansas 42. Iowa 43. Nebraska 44. Kentucky 45. Maine 46. Vermont 47. Ohio 48. Rhode Island 49. New Jersey 50. New York Nebraska received high marks only for its fairly low unemployment costs. @ 14th in the country Add on to the unfavorable tax climate, NEbraska's high worker compensation medical costs, and we are overdue for reform.

Scottsbluff police search warrant for narcotics in duplex lacked probable cause to search separate apartment, but Nebraska Court of Appeals (J Irwin) allows evidence on Leon "good faith." State v. Tompkins, 14 Neb. App. 526

Filed February 28, 2006. No. A-05-212. Police obtained search warrant for suspected narcotics activity in a Scottsbluff duplex, based on citizen reports of suspicious activity, police surveillance and searches of garbage from duplex. Court of Appeals found that search warrant lacked probable cause because although police had information of suspcious activity, there was no probable cause to search the defendant's apartment in duplex. Still police had good faith belief that warrant was valid and court allows evidence; Court found that issue of probable cause for searching entire duplex was an open question at the time of the searc.

At the time of the issuance of the search warrant in this case, no Nebraska case directly on point existed regarding an issue of first impression: whether, in the context of facts such as those of the present case, an affidavit in support of a search warrant for multiple individuals and multiple residential units contains a substantial basis for determining that there is probable cause specific to one of those individuals. We cannot conclude that a law enforcement officer who had reasonable knowledge of what the law required regarding probable cause relating to multiple suspects and multiple residential units would, at the time of the execution of the search warrant in this case, have been unreasonable in relying in good faith on the warrant issued by the magistrate in this case. Additionally, the information Overman presented to the issuing judge was not completely devoid of indicia of probable cause, and such information, viewed as a whole, arguably supports the conclusion that there was a fair probability that evidence of illegal drug activity would be found at Tompkins' and Snow's residences. See, United States v. Leon, 468 U.S. 897, 104 S. Ct. 3405, 82 L. Ed. 2d 677 (1984); State v. Davidson, 260 Neb. 417, 618 N.W.2d 418 (2000); State v. Edmonson, 257 Neb. 468, 598 N.W.2d 450 (1999). Therefore, we conclude that there was an objectively reasonable basis for believing that the warrant was valid.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)